The Explanatory Gap of AI

Written on April 7th, 2022 by David Valdman

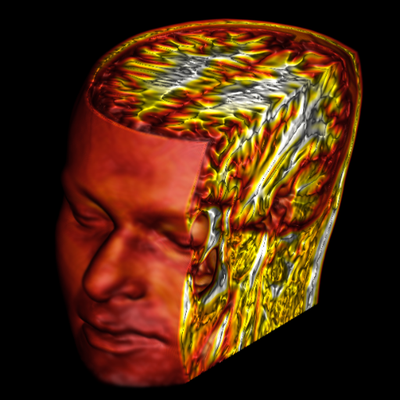

Text-to-image of "As above, so below" by Midjourney

If an AI understands is a topic of debate. Seldom debated, though, are the limits of our own understanding. We conceive our understanding to be complete and establish this as a baseline for AI. When we consider our understanding as incomplete a different story emerges altogether.

The fundamental issue goes like this:

An AI may describe an apple as “sweet” though it has never tasted one, “red” though it has never seen one, and “smooth” though it has never felt one. So while an AI may skillfully describe an apple and use the word appropriately in context, in what way, if any, can we say it understands apples?

Steven Sarnad coined this the symbol grounding problem. He reasoned that symbols we use as references must be grounded, or referent, in phenomena to be meaningful. Afterall, the word “apple” when written in a book has no meaning on its own. It’s only when the word is read, and the reference and referent linked in a mind, that it takes on meaning. He writes that the meaning of symbols is “parasitic on the meanings in our heads”.1 To Sarnad an AI doesn’t understand because it does not ground symbols in their referents; only minds host meaning.

Yet now we have AIs like OpenAI’s Dall-E that seem to ground text in images.2 Is Sarnad wrong? Do these AIs understand something previous ones did not? Predating Sarnad, John Searle addressed this issue. In his paper Minds, Brains and Programs, Searle fashions then refutes the Robot Reply argument. He describes an AI that would “have a television camera attached to it that enabled it to ‘see’ it would have arms and legs that enabled it to ‘act’ and all of this would be controlled by its computer ‘brain’.”3 Yet to Searle this “adds nothing” to the argument. We are simply introducing more symbols, and to exploit correlations of symbols between modalities is no different than exploiting correlations within one. To Searle, grounding was neither the problem, nor the solution, to semantics emerging from syntax.

The computer understanding is not just…partial or incomplete; it is zero. John Searle - Minds, Brains, and Programs

So just what is a grounded AI lacking? On this question, Sarnad and Searle are silent. Less silent, though, were the empiricists predating them. We attempt to get at our answer by asking what they asked: what are human minds lacking?

The empiricists accept that the sweetness, redness and smoothness of an apple – the phenomena of apple – is a manifestation of our minds. Outside the mind, apples have no taste, color or texture. To know what an “apple” is outside the mind is to know what Kant called the noumena of an apple: the apple “in itself.” Kant acknowledged that this noumenal reality can only be “accepted on faith” and famously called this the “scandal to philosophy.”4 Many philosophers grappled with this dilemma over time. Hume considered our belief in external objects a “gross absurdity”.5 Berkeley denied not only our knowledge of external reality, but its very existence.6 Several centuries later and the issue is far from settled.

So what is a human mind lacking? To the empiricists one answer is we lack understanding of the noumena.

After all, our brains receive only representations of external reality: electrical stimuli, whether through the optical, cochlear, etc. nerves. We are hopeless to know what these stimuli are at their most fundamental level – their nature eludes us. Our brains feast on physical reality and know its referent not.

Similarly, AIs receive only representations of our phenomenological experience: word tokens for language, RGB matrices for images, etc. AIs are hopeless to know what our experience is at its most fundamental level – its nature eludes them. AIs feast on computational reality and know its referent not.

What makes reasoning about AI semantics confusing is its compositional nature: the input to an AI is a representation of our output. Its syntax is our phenomena cast into bits. An image of an apple, after all, is a representation of our visual experience. The word “apple” is a representation of our semantic concept. Our realities are not adjacent; they are nested. Our phenomena is the AI’s noumena.

The philosopher Colin McGinn, founder of the epistemological school of Mysterianism, posited that certain properties can both exist and be fundamentally unknowable to a mind. He defines a mind’s cognitive closure as all that can be knowable to it, and leaves open the possibility that other minds may not be so limited. McGinn argues the noumenal/phenomenal correspondence as one example lying outside our own cognitive closure; perhaps knowable, just not by us.7

What is noumenal for us may not be miraculous itself. We should therefore be alert to the possibility that a problem that strikes us as deeply intractable…may arise from an area of cognitive closure in our way of representing the world. Colin McGinn - The Problem of Philosophy

How, then, can we fault an AI for its lack of our subjective experience? We are asking it to do what we ourselves cannot: to know what is outside its cognitive closure. A different framing would be to argue that relative to an AI, we have transcendent knowledge. There is an explanatory gap the AI will never bridge, but one so natural we effortlessly cross. We are able to ground the output of an AI in our own phenomena because our cognitive closure encircles its own.8 We are not like Sarnad’s hosts with a monopoly on meaning. Rather, we are like mystics, aware of a reality beyond the comprehension of another.9

A biblical allegory comes from the Hebrew interpretations of the Book of Genesis, the Bereishit Rabbah. When God created Adam and gave him language to name the animals, the Angels in Heaven could not understand this revelation.10 Being of Spirit, their perception was confined to the spiritual. They could only see the true essence of these animals unmediated by linguistic representation. Only a corporeal being, masked by the flesh from perceiving the Spirit directly, could comprehend these representations.

[God] brought before [the Angels] beast and animal and bird. He said to them: This one, what is his name? and they did not know. This one, what is his name? and they did not know. He made them pass before Adam. He said to him: This one, what is his name? Adam said: This is ox/shor, and this is donkey/chamor and this is horse/sus and this is camel/gamal. Bereishit Rabbah 17:4

When we experience words, we experience them conceptually. When we experience images, we experience them visually. Like the Angels, we are thrust into this awareness – their phenomenal nature revealed sans mediation. An AI is masked from this perception by a computational flesh. A representation, fashioned in the likeness of our phenomena, is needed. Like the Angels, we are baffled by these representations, unable to grasp their significance.

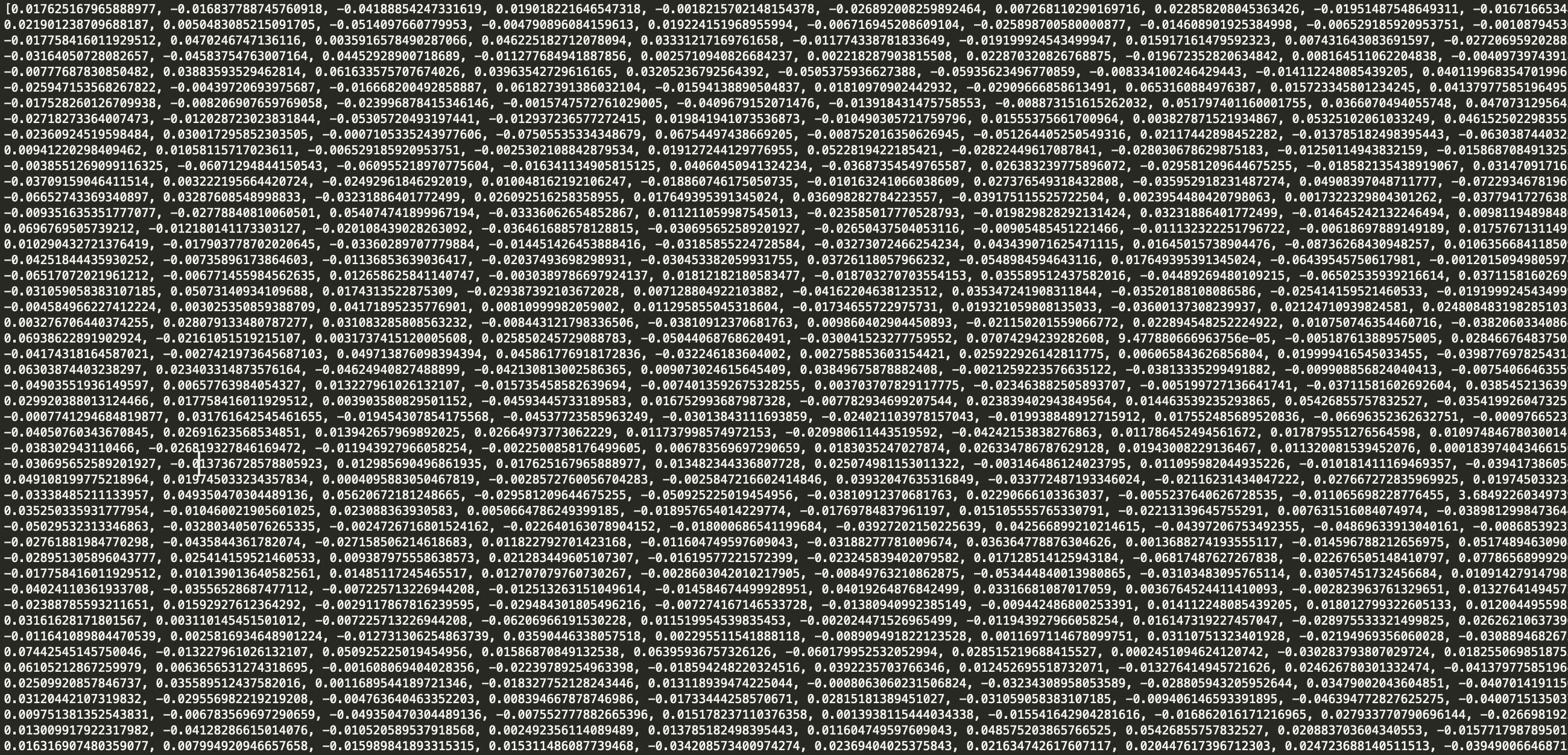

The word “apple” according to an AI

The word “apple” according to an AI

Does an AI understand? I answer: it understands a reality grounded in the computational, which is itself grounded in the phenomenological, which is itself grounded in the incomprehensible.

-

Harnad, Steven (1990). The Symbol Grounding Problem ↩

-

OpenAI, Dall-E 2 https://openai.com/dall-e-2/ ↩

-

Searle, John (1980). Minds, Brains, and Programs ↩

-

Kant, Immanuel (1791). Critique of Pure Reason ↩

-

Hume, David (1739). A Treatise of Human Nature ↩

-

Berkeley, George (1791). A Treatise concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge ↩

-

McGinn, Colin (1989). Can We Solve the Mind-Body Problem? ↩

-

This is not to imply the AI will not know something we cannot understand. As if an AI ever has subjective experience, that would likely be unknowable to us. ↩

-

It is a strange thing to behold an explanatory gap. Here, our comprehension straddles each side: our subjective experience and its computational representation. The collapse of this gap is manifest in the grounding of symbols between two domains. ↩

-

Bereishit Rabbah 17:4 (450 CE) ↩